The Movie (1967): Stanley Moon (Dudley Moore) is a cook at a fast food place. Nervous, dissatisfied with his lot in life and somewhat lacking in social skills; Stanley is deeply in love with his co-worker, Margaret Spencer (Eleanor Bron). Of course, he is too scared to make conversation, and his attempt to ask her out goes badly.

A disastrous and humiliating suicide attempt is where he meets Satan, aka. George Spiggott (Peter Cook). The Devil offers Stanley a chance to get everything he’s ever wanted; seven wishes, whatever he asks for, in exchange for his soul. Of course, this being the Devil, Stanley’s wishes always turn out the exact opposite of what he’s after. With each failed wish, Stanley desperately attempts to outwit George; but the Devil and his servants, the Seven Deadly Sins, are always a few steps ahead…

The Movie (2000): Elliot Richards (Brendan Fraser) is unable to relate to people, though he desperately wants to. He tries to fit in and make friends, but he has trouble reading social cues and tends to try too hard. As a result; all his co-workers loath him and give him a hard time and he is unable to approach Alison Gardner (Frances O’Connor), the woman of his dreams. In short, Elliot is lonely and miserable.

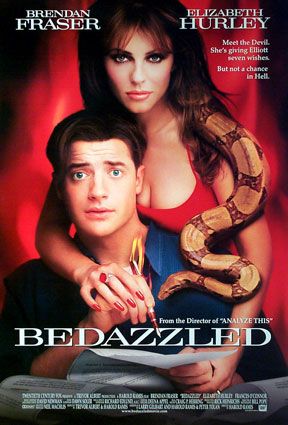

Then one night in a bar, Elliot meets the Devil (Elizabeth Hurley). The Devil offers him a way to solve all of his problems and win Alison; in exchange for his soul she will give him seven wishes. But as the old saying goes: “be careful what you wish for, you just might get it;” and what you get might not be what you truly wanted in the first place…

Compare and Contrast: And now for something completely different, as Monty Python used to say. For this review I am going to try an idea I got from some other web sites; I will compare and contrast the movie Bedazzled and its remake. This was probably inevitable, as the majority of Hollywood’s works these days are remakes. This is an experiment, so I’m not sure how well it’s going to go. Feedback on this would be most welcome. A small warning, there will be some spoilers in this review, probably a few major ones. One more note is that I will make references to “God” as written. This isn’t a slight of anyone’s beliefs, but a concession to my own; as I tend to lean toward the polytheist end of things. No offense is meant to anyone; though I’m sure there are those who will take it just the same.

My parents have long been fans of the original Bedazzled. In fact, one of my oldest memories is of watching part of it with them on television. However, it never came out on video until the remake, so it wasn’t until late high school/early college that I got to see it. While Bedazzled is very much a product of its times, and I hesitate to call it a classic; it is definitely a very fun, well made movie. It’s obviously the result of intelligent people with a rather warped and cynical sense of humor; my kind of art.

As for the remake, it’s almost as good. I really shouldn’t have to be surprised at this; but in this age of remakes I have started to become burned out on the things. After seeing the remake of Karate Kid (which, gods help me, I may cover one day), which steals all of the best parts and major plot points of a good movie with no clue whatsoever of why they were so effective; it’s refreshing to watch a competent remake. The 2000 version of Bedazzled does follow the same basic plot structure; it even borrows a few major plot points from and makes a few obvious winks and nods to the original. However, the completed work is very much its own movie.

Probably the first major point of departure of the two movies is the general tone of the humor. The original Bedazzled is British humor; dry, acerbic and understated even as more outré events happen. Much of the comedy is based on witty lines, word-play and innuendos. The remake, being Hollywood, is much more blatant and outrageous. For an example, a comparison between the two movies’ handling of one the few wishes they both featured should suffice.

In the original, Stanley’s second wish is to be a multimillionaire and married to Margaret; who he wants to be very physical and affectionate. In true Faustian fashion, Margaret is very physical and affectionate with everyone but Stanley. Most of the humor comes from Stanley trying to keep his cool while Margaret is visibly cuckolding him in front of everyone. George, Stanley’s friend and business associate in this wish, makes all sorts of subtle innuendos about the situation which Stanley desperately tries to ignore or pass off. It finally ends when George betrays Stanley with Margaret and Stanley decides it is just too much. There is also the small element that Stanley gets his wealth from arms deals, although it’s only presented as a minor detail.

In the remake, Elliot’s first wish is to be rich, powerful and married to Alison. The situation with his wife is similar; she hates her husband and is very obviously having an affair with one of his underlings. However, most of the humor comes from Elliot’s revelation about where his wealth and power come from; he’s a Colombian drug lord. Elliot’s cuckolding and moral uncertainty about his business causes one of his minions to rebel against him, and the resulting explosive (literally) shootout prompts Elliot to cancel his wish.

The heroes of the respective movies have some slight variation on each other. Stanley Moon is kind of a nebbish wallflower; he can’t relate to other people and is too afraid to try. Elliot Richards, on the other hand, has the opposite problem. He does try, but he works so hard at being what he thinks other people want him to be that he overcompensates. The differences fit into the general spirit of the two films; in the original Stanley is pretty much the helpless everyman who is constantly stepped on by the impartial forces that rule his world. Elliot, on the other hand, can’t or won’t understand what he needs to do to have control of his life.

Peter Cook’s George Spiggot, aka Satan; puts some interesting spins on the character of the Devil. For one thing, he pretty much personifies the definition of “frienemy.” All throughout the movie he alternates between being friendly and sympathetic to Stanley on one hand, nasty and insulting on the other, switching between the two at a whim. He constantly tries, successfully, to trip Stanley up on his wishes. Every so often he offers a gesture of seeming kindness and generosity, but there is always an ulterior motive.

George appears in all of Stanley’s wishes as well. When he does, he is almost always the spoiler element. In the wish I went over above, for example, George is the friend who commits the final betrayal of Stanley with his wife. In another one, where Stanley wishes to be a famous pop star, George is the upcoming rival who steals the spotlight from him. They only times when this isn’t the case is when either the wish itself is stacked against Stanley, or Stanley is obviously going to screw himself over and needs no outside help to do it.

A final, interesting twist to George’s character is what he does between Stanley’s wishes. Whenever Stanley cancels a wish, he spends the time tagging along with George as he does his job. What’s interesting is that George rarely does anything blatantly evil or destructive. Instead, he does things like scratching records and tearing the last pages out of mystery novels before selling them, training a pigeon to poop on a man’s hat, or calling wrong numbers to people who are in the tub. His actions are definitely petty, mean-spirited and irritating, but they can’t really be called evil.

Elizabeth Hurley’s Devil is very different. For one thing she’s female, which lends a sexual vibe to her and her actions (I don’t understand why female evil tends to be linked to female sexuality in the popular mindset, but there you are). Also, her between-wish actions tend to be more blatantly destructive; things like causing car accidents and giving candy to hospital patients instead of their pills. However, she’s not quite as nasty toward Elliot as George is to Stanley. In fact, when she tells him she likes and cares about him, it’s very easy to believe her even though she is trying to trip him up.

Another interesting difference is the Devil’s influence in Elliot’s wishes. She appears in a few of them, but always in the background. For example, in Elliot’s wish to be an NBA star, we catch a glimpse of her leading his team’s cheerleaders. However, she never directly affects the wish herself. It’s always either the wish, or it’s Elliot himself, or some combination of the two that is responsible for it failing.

My final contrast between the films, how the contract is resolved and how “God” is depicted, are what ultimately define the movies’ tone and viewpoint. In the original, George tells Stanley early on that he has a bet with “God” about who can get a certain number of souls first. He’s almost there, and if he wins he gets back into Heaven.

Later on, Stanley’s is stuck in his last disastrous wish and catches George just as he’s about to leave for Heaven. On a whim, George decides that returning Stanley’s soul would make an impressive magnanimous gesture. Unfortunately for him, “God” decides that George’s motives are suspect and doesn’t let him back in after all. Just before the credits roll we have George shouting at the sky, threatening to screw up the world so much “God” Himself will be ashamed. His only response is “God’s” evil laughter.

Stanley ends the movie back where he started at the beginning. All he has to show for his trials are several lifetimes of experience; and the knowledge that he has to get what he wants himself, with no supernatural help. What he will do with this knowledge, or whether it will even be of use to him at all, is left hanging. Bedazzled leaves us with a grim cosmology, one where we are insignificant pawns in a game between formidable but indifferent forces, and where we have little power to change things for ourselves.

In the remake, Elliot, with one wish to go and realizing that he’s screwed, attempts to get out of the contract and winds up in jail for the night. He finds himself sharing a cell with a man who tells him exactly what he needs to hear; he can’t sell his soul, it’s within his power to change his life, and that if he tries he will get to where he needs to be. Elliot tells the Devil he doesn’t want his last wish. She tries to scare him into it with a vision of Hell and Elliot, deciding he’s screwed anyway, wishes for Alison to have a happy life. When he comes to, the Devil tells him that there is a loophole in the contract that voids it if he does anything truly selfless.

Elliot’s experiences gives him the strength to not let his co-workers walk over him and to ask Alison out. It turns out she’s taken, but he gets a new neighbor, Nicole, who’s her exact duplicate. At the end of the movie, it’s obvious that things are going very well between the two of them.

The remake’s cosmology is very different from the original. In this one, human actions and choices are what’s really important; the Devil tells Elliot as much at the end. Likewise, while there are powers trying to trip us up (i.e. the Devil), there are other ones who are trying to help us. We are left in no doubt as to the identity of Elliot’s cellmate; one of our last glimpses is of him and the Devil playing chess in the park. Even the Devil isn’t too bad, and what she can do to us is limited by the choices we make for ourselves.

In ending, I would say that the original Bedazzled, from a technical and artistic standpoint, is the better movie. On a personnel note, it’s also the one that fits my world view. However, I actually like the remake better. This is because the remake’s point of view is the one I want to believe in. Both are very much products of their times (especially the original), but both are also very much their own movies and worth seeing.

No comments:

Post a Comment